Why Every Strategy Needs a Formula, Not Just a Slide

Visual clarity matters — but only structure makes strategy simple

Harvard Business Review recently published an article titled “You Should Be Able to Boil Your Strategy Down to a Single Clear Visualization.” The authors make a persuasive argument: leaders who can express their company’s strategy in a single image communicate more effectively, build alignment faster, and even influence market confidence. They cite data showing that investors respond more positively when presentations include a visual depiction of the strategic rationale behind a decision.

“When presentations were accompanied by a slide illustrating the strategic rationale for a deal, investors were more than twice as likely to give it an immediate thumbs-up,” the authors write. “Employees could pin it on their office walls, and it could serve as a foundational slide for any presentation of a strategic recommendation they’d like to make.”

The premise is sound. Visual clarity does drive strategic clarity. But what matters most is not visualization, but clear logic. A strategy is only as clear as the structure that underpins it. Compressing a complex model into a single elegant diagram may look simple, but true simplicity requires more than graphic restraint — it requires structural coherence.

To make strategy truly elegant, you have to make its logic visible.

Prefer to listen? Here’s the audio edition of this post:

When Visual Simplicity Becomes Strategic Confusion

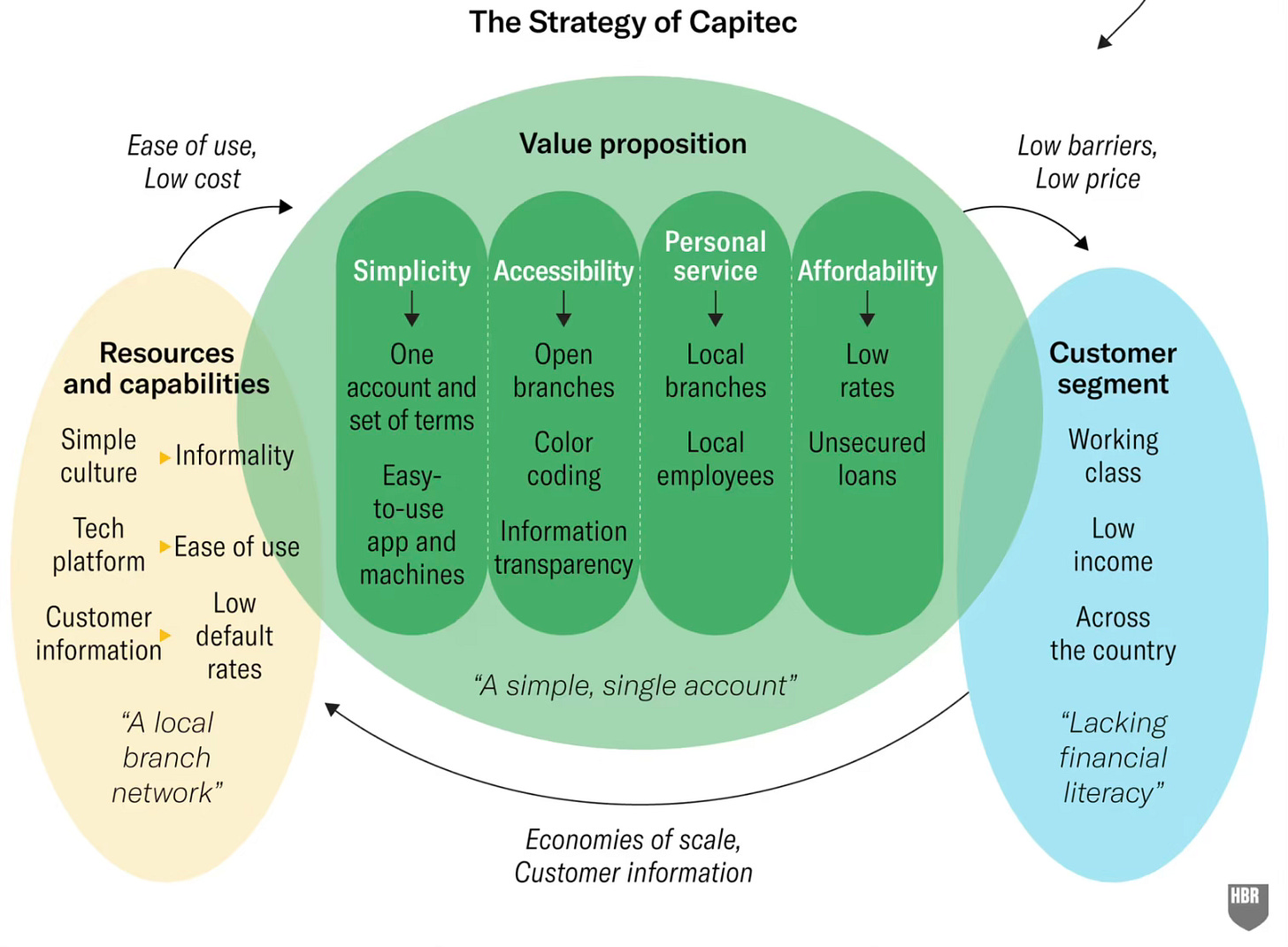

The HBR article features a case study of Capitec Bank, a South African retail bank known for serving lower-income consumers. The visualization is beautiful at first glance — overlapping ovals labeled “Resources and Capabilities,” “Value Proposition,” and “Customer Segment,” each filled with descriptors and arrows showing relationships.

It looks like clarity, but it isn’t. Every oval, color, and arrow adds more data, but none define the underlying structure of the business. Does Capitec make money by selling services, renting access to capital, or both? Is it differentiating through cost, service, or segmentation? The visual gives us content but not coherence.

It’s as if someone decided a ten-slide deck was too complicated, so they compressed all ten slides into one and declared victory. That’s aesthetic simplicity, not strategic simplicity.

What looks like clarity is really compression. The problem isn’t design — it’s missing structure. The question is how to recover it.

How Structure Restores Clarity

Design can simplify communication, but only logic can simplify strategy. In my work, I use the Periodic Table of Business Strategy™ to distill every business into a single equation:

This is the company’s strategic formula — the clearest expression of how it creates and defends value.

Each element has a distinct purpose. The Business Model defines how the firm is structured and earns revenue. The Strategy captures its posture in the market — how it chooses to compete, serve customers, and respond to rivals. The Advantage reveals whether those choices produce a durable moat or simply keep the company at competitive parity, where disciplined execution sustains results but does not protect them.

The formula doesn’t replace visualization; it gives it structure. Once a leader can express their model, strategy, and advantage in these terms, any visual built on top becomes an act of communication rather than decoration.

Revealing the Real Business Model

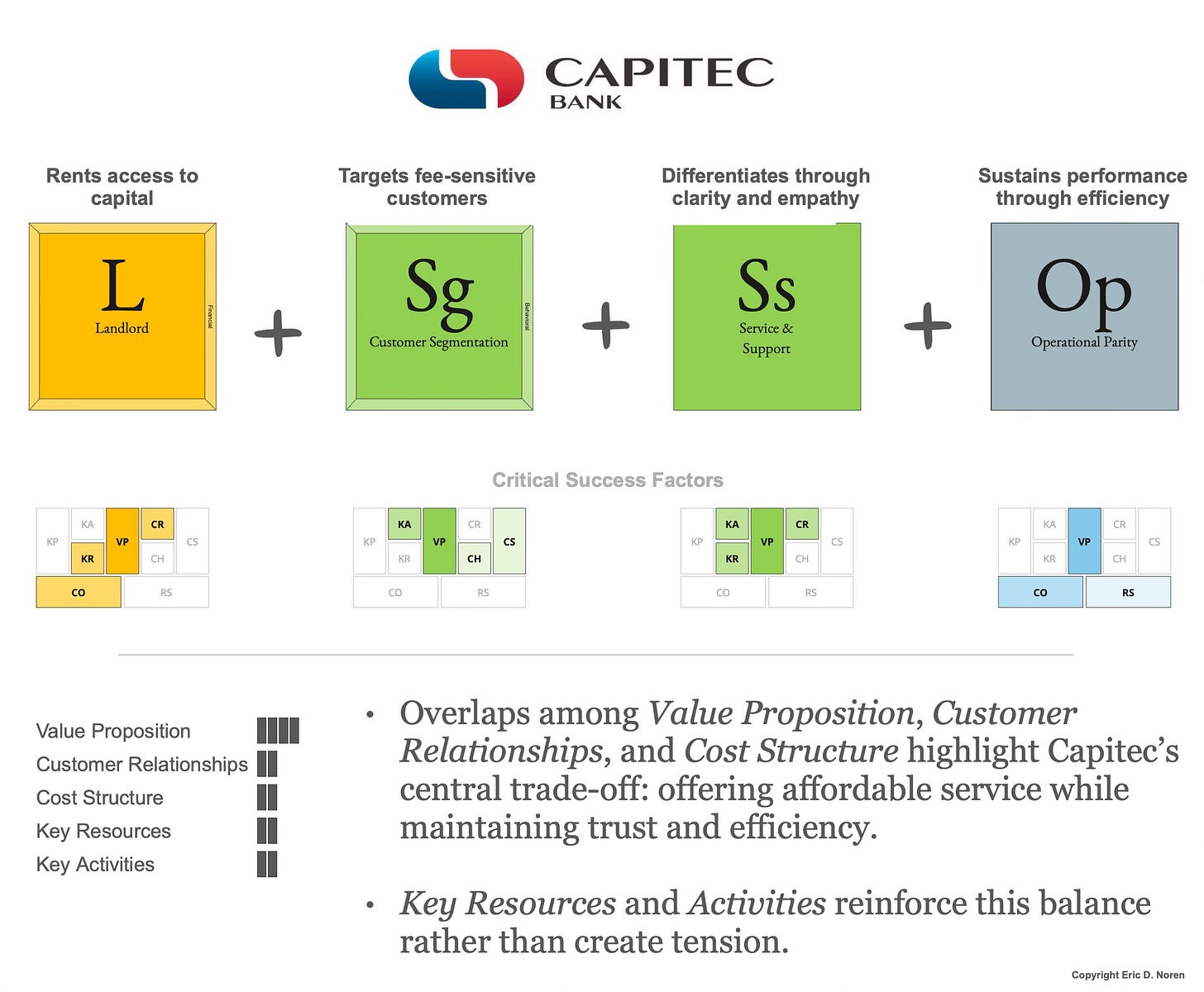

Seen through my system, Capitec’s structure becomes far easier to express. The bank serves low-income, fee-sensitive consumers through local branches. That might look like a Traditional Retailer [Rt], but economically, Capitec behaves more like a Landlord [L] — renting access to money in the form of loans. The retail façade supports a financial core.

Its primary strategy is Customer Segmentation [Sg], focusing on an underserved population, reinforced by Service & Support [Ss], which emphasizes simplicity, transparency, and human trust. The company executes exceptionally well but holds no moat that others cannot replicate — hence Operational Parity (No Advantage) [Op].

Formula:

In plain language: Capitec rents access to capital for a fee, targets an underserved customer segment, competes through simplicity and service, and sustains performance through disciplined execution. (Note: Since Operational Parity is not a true advantage, it is additive to the strategic formula and does not serve as a multiplier.)

What the elaborate visualization expresses in multiple boxes, this formula conveys in a single line. It captures both the surface narrative and the underlying economics — and it exposes a subtle truth the diagram hides: Capitec’s strategy isn’t simple. It’s compound, combining multiple plays that coexist uneasily. The formula doesn’t judge that complexity; it illuminates it.

This distinction between presentation logic and profit logic lies at the heart of strategic clarity. Many companies describe themselves as something they are not. Banks portray themselves as retailers; cloud providers call themselves software firms while behaving like landlords; streaming platforms talk like media companies but function as retailers bundling access to licensed content.

The strategic formula resolves that confusion by forcing a direct statement of how value actually flows. By naming the model explicitly, leaders can separate what the company appears to do from what it really does. Every choice — pricing, partnerships, growth — depends on that recognition.

In Capitec’s case, that simple insight shifts the entire analysis. It is not a retail bank pursuing low fees; it is a landlord managing capital flows within a defined customer niche. The visual never makes that distinction clear, but the strategic formula does.

The HBR authors list “Economies of Scale” and “Customer Information” as if they are established sources of advantage. They might be — someday. But that phrasing reflects a deeper problem: diagrams like this often blur the line between aspiration and reality. In my system, both belong to the category of competitive advantage — a structural condition that must already exist, not one a company merely hopes to achieve. A visual that implies Capitec already commands these moats risks sowing confusion, mistaking strategic intention for structural fact.

What the slide hides in color and shape, the formula reveals in structure. But recognizing structure is only the first step; the real advantage comes from seeing how those structures interact — and where they strain against each other.

Making Complexity Coherent

Most modern strategies are hybrid by design. Platforms double as manufacturers; retailers operate media networks; and subscription models cross-subsidize physical goods. The AI era amplifies this tendency, blurring boundaries between data, product, and service. Yet visual frameworks often treat complexity as a formatting problem — something to be arranged more neatly — when it is, in fact, structural. Their beauty can disguise incoherence.

My strategic formula system takes the opposite approach. It acknowledges when multiple logics coexist — (L + Rt + Ss), for example — and makes their interactions visible. A Landlord [L] rents access to a scarce asset, earning income from usage or time. A Traditional Retailer [Rt] sells discrete products at a markup, relying on margin and inventory turnover. Service & Support [Ss] differentiates through human relationships and responsiveness rather than efficiency or scale.

Combined, these logics can reinforce one another in small doses — say, when a financial institution like Capitec uses retail branches to deliver trust-based service while managing lending capital behind the scenes. But they can also conflict. The Landlord model seeks to minimize human touch and standardize risk; the Retailer depends on high transaction volume; and the Service & Support strategy prizes empathy and personalization, which raise costs. Most strategy visuals blur these trade-offs into a single harmony of color and shape. The formula makes the friction visible: when a business tries to be efficient, personal, and high-volume all at once, coherence — not creativity — becomes the constraint.

A company’s strategy can still be multifaceted and clear, provided its elements are logically aligned. The strategic formula gives leaders a shared language for that alignment — a way to describe hybridity without resorting to diagrams that collapse under their own weight.

In short, the strategic formula doesn’t hide complexity — it renders it readable.

Understanding coherence is only half the work. Once the logic is visible, the next challenge is execution: translating that clarity into the few operating factors that determine whether the formula succeeds or fails.

Turning Logic into Execution

A strategy expressed as a formula is concise, but not thin. Once defined, each element of the Periodic Table of Business Strategy carries its own Critical Success Factors — the execution conditions that determine whether the strategy works in practice. These are the day-to-day mechanisms through which structure becomes performance. My system draws on the language of the Business Model Canvas to describe them: Key Resources, Value Proposition, Revenue Streams, and the other essential blocks that translate intent into execution.

For Capitec’s formula — L + Sg + Ss + Op — several of these factors overlap. The company behaves as a Landlord [L], renting access to capital; it competes through Customer Segmentation [Sg] and Service & Support [Ss]; and it sustains results through Operational Parity [Op]. Each element introduces a distinct execution logic, and together they explain both the company’s strength and its structural tension.

Landlord [L]. Capitec depends on managing a pool of capital efficiently. The critical factors are Key Resources — loanable funds and credit discipline; Value Proposition — affordable, transparent access to money; Customer Relationships — trust that borrowers will repay and depositors will stay; and Cost Structure — keeping funding costs and defaults low. The model rises or falls on prudent lending and liquidity control.

Customer Segmentation [Sg]. The bank focuses on a defined behavioral niche: lower-income, fee-sensitive consumers. Its key factors are Customer Segments — knowing this audience deeply; Channels — maintaining accessible branches and digital tools; and again Value Proposition — banking that feels fair and human; Key Activities — tailoring product design, communication, and delivery to the needs and behaviors of fee-sensitive customers. Execution depends on localization, behavioral insight, and consistent delivery of simplicity.

Service & Support [Ss]. This layer emphasizes customer experience rather than pricing. The essential factors are Key Activities — responsive service and problem resolution; Key Resources — well-trained frontline staff and intuitive digital tools that embody the brand’s promise of simplicity; Value Proposition — clarity and empathy; and Customer Relationships — trust built through human interaction. The brand’s promise depends as much on the quality of conversation at the branch as on the ease of its technology.

Operational Parity [Op]. Because the company holds no enduring moat, it must continually improve efficiency. The key factors are Cost Structure — lean operations; Revenue Streams — steady, low-margin interest and fee income; and again Value Proposition — consistent reliability. Sustaining parity requires constant vigilance: continuous cost management, process refinement, and disciplined execution.

Across these four elements, the overlaps tell their own story. Value Proposition appears everywhere, showing how much weight the brand’s promise of simplicity must carry. Customer Relationships and Cost Structure recur too, exposing the constant tension between personal service and operational efficiency.

Capitec’s strategy looks complex because it is complex. It asks the organization to be simultaneously low-cost, high-trust, locally attentive, and operationally disciplined. The HBR visualization captures these ideas graphically, but it cannot show how they compete for resources and managerial focus.

The strategic formula renders complexity visible; the critical success factors translate it into action. Together, they define the organization’s focus — trust, simplicity, and cost control; its tension — balancing service quality and efficiency; and its risk — capital management, customer default, and scale expansion.

Rather than stripping information away, the formula and its success factors recover what the visualization obscures. The difference is precision: a short list of operating priorities replaces a maze of arrows. What remains is not less information, but a clearer hierarchy of what truly matters.

Strategic Insight:

Capitec’s simplicity depends on a single promise repeated across elements: Value Proposition.

Its greatest strength and tension lie in balancing trust, empathy, and efficiency.

The formula reveals what the visual obscures: clarity through structure, not compression.

From Slide to Sentence

The HBR authors are right that a strategy should be communicable on a single slide. But that’s only the surface layer. The real test of clarity is whether it can be written as a single line of logic — and executed through a small set of critical factors that everyone understands — then shown visually in a way that clarifies the logic instead of hiding it behind design.

A leader who can express their company’s formula knows what the business is built on and why it works. A leader who can name the critical success factors knows how it runs and where it breaks. Together, the formula and its critical success factors form a complete bridge between strategy and execution — conceptual clarity matched by operational discipline.

So yes, simplify the slide — but also simplify the system.

(Business Model + Strategy) × Advantage → Critical Success Factors

The simplest visualization of all — the logic of how you win, and the levers that make it real.

Canonical definition: Strategic Formula System.

Note: The visualization of Capitec Bank referenced here appears in “You Should Be Able to Boil Your Strategy Down to a Single Clear Visualization” (Harvard Business Review, July 2025).

About the author: Eric D. Noren is VP of Digital Operations & Growth at Foundation Partners Group and the creator of the Strategic Formula System, including the Periodic Table of Business Strategy™, the AI Susceptibility Index™, and Learning-Loop Economics™. Learn more at ericdnoren.com.

AI Disclosure: This essay is fully conceived, argued, and structured by me. I use AI tools as a research and drafting partner, but the strategic ideas and final decisions are my own.

Exceptional critique of how visual compression can mask strategic incoherence. The Capitec example nails it when you point out they're esentially a Landlord pretending to be a Retailer the HBR diagram obscures that economic reality behind colorful ovals. I've seen this pattern in tech companies too where SaaS firms present as software businesses but their unit economics look more like subscription landlords. The formula approach forces honesty about what business you're actually in. That overlap analysis showing Value Proposition appearing across all four elements is particularly telling, it reveals the massive execution burden they're carring. One thing I'd add is that formulas also make it easier to spot when strategy shifts are happenning versus just surface-level pivots.